The apocalypse is all the rage these days. Blown up, devastated, ruined, and post-nuclear worlds are as inescapable as the inevitable doom these glorious nightmare scenarios envision. It seems there’s something about imagining humanity’s demise that has captured our collective attention of late.

The apocalypse is all the rage these days. Blown up, devastated, ruined, and post-nuclear worlds are as inescapable as the inevitable doom these glorious nightmare scenarios envision. It seems there’s something about imagining humanity’s demise that has captured our collective attention of late.

We’ve squeezed the apocalyptic fruit of so much juice that it seems to have nothing left to give. The apocalypse has become boring. How’s that for strange?

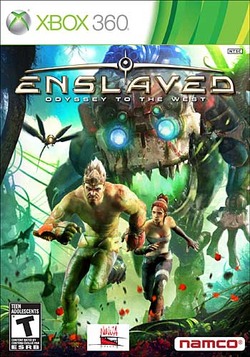

Enslaved manages to infuse this overdone concept with new life by abandoning the bland brown grit traditionally favored as the end of the world’s color of choice. Instead, it opts for a greener palette, one that sees nature as regaining its rightful control over the land after humanity has made itself scarce.

While Enslaved dazzles with its unique setting, it decidedly lacks a historical focus. Those hoping to learn the details of this world’s downfall will be disappointed. Enslaved plants its foot firmly in its fictional present and you learn little more than vague hints of backstory throughout the course of the adventure.

The game finds its true strength in its characters. The world sometimes seems a confusing jumble of disparate elements, full of lush greenery and sentient robots alike, but the characters you encounter along the journey, while few in number, will quickly endear themselves to you. By the end of the game, you’re sure to care far more about the people than the land.

This is perhaps fortunate, as the game mostly ignores its own backstory. I admire this approach in a way, as needless exposition is rarely a sign of good storytelling. This is a human tale, unlike so many others set after society’s downfall that seem more a lesson in fictional history than relatable account of those that survived. Still, with a setting this unique I can’t help but be disappointed that there’s nothing more here to chew on. So many fascinating aspects go unexplained that it left me with an equal sense of mysterious wonder and emptiness.

Enslaved’s story begins as a journey home in a land where “home” is a foreign concept to some. One such man is the character you take control of, a lone traveler type who accepts the name Monkey while insisting he has no true name. Monkey and a young woman named Trip escape from a slave ship in a thrilling sequence at the beginning of the game. Soon afterward, Monkey finds himself knocked unconscious by a rather uncomfortable landing.

When he wakes up, he has a fancy new accessory wrapped around his head. Trip, you see, is rather anxious to get home; enough so that she has essentially turned Monkey into her personal slave. The headband she has placed on him forces him to do as she asks. More importantly, it means that if Trip dies, so does Monkey. So, with little recourse, Monkey agrees to help Trip get home so he can go free.

This is an awkward situation for both characters and the game makes full use of it. Monkey obviously doesn’t like being controlled, but, more interestingly, Trip doesn’t seem to like doing the controlling. She legitimately feels for Monkey and it shows, but she simply felt the headband was her only option to survive the trip home. This setup creates an endearing tension between the two characters that is the primary focus of the game. Suffice it to say, the story continues after the two reach Trip’s home, but where the story goes from there was far less interesting to me than simply continuing to spend time with the two to see how their relationship developed.

Enslaved borrows heavily from the Uncharted school of game design. It consists almost entirely of fighting and traversal. Combat is simple but effective with a heavy focus on melee. Too much is occasionally asked of your abilities, especially when dealing with multiple enemies at once as becomes quite common as the game progresses, but the difficulty curve isn’t particularly high so it’s rarely problematic. Traversal is almost identical to Uncharted’s in that the focus is less on precise timing and player skill than on spectacular leaps from place to place and breaking up the action with a bit of heavily guided exploration.

Here Enslaved reveals what is perhaps its biggest flaw. The overbearing hand of the developers overshadows the entire experience. From the first level to the last, you are never off of the rails. The game guides you forward with unceasing rigidity. You are never free to explore and find your own way. Never are you let off the leash to wander the lush world. When Monkey is forced to leap about like a Persian prince, every handhold is quite literally highlighted for you and it’s impossible to make a wrong move. Before you start each level, your path will be clearly shown to you and, through Trip and some clever story justification, you will be told exactly what to do at all times. Surrounded by such vibrant environments, such domineering design makes the experience feel overly limited and cramped. It confines a game that begs to be expansive.

The end result isn’t disastrous, just disappointing. This is a game that could deservedly be called fun far more often than not, but it never escapes the feeling that it could have been something even better.

What the developers have done is placed a heavy burden on the story. Mechanically, the game is a roller coaster. It’s exciting but so highly guided that player input amounts to little more than the power source that keeps the story flowing forward. This is fine as long as the action is suitably spectacular, which it usually is, and as long as the story continues to provide a compelling reason for the player to keep pushing his own car down the roller coaster track.

Here we have a bit of a problem. Enslaved has a rather unique conundrum. With many story-heavy games, the narrative arc overshadows the characters. This is an all too common problem in the spectacle-heavy world of video games. Rarely, however, do you find compelling characters in a bland adventure. Games are so poor at characterization that this just doesn’t happen, but this is precisely Enslaved’s issue.

While the game is keeping its focus on the characters, things are fine. Through the first half the game, as Monkey helps Trip get home and, subsequently, deal with what she finds there, everything goes swimmingly. Afterwards, the story veers toward that of a revenge tale. This has the unfortunate side effect of placing a greater focus on the world surrounding the characters, the one which it had been so far doing a terrific job of keeping vague and out of the way. I’d hardly call this second half of the story terrible, but it definitely doesn’t play to the game’s strengths. I found myself not much caring about the newly adopted end goal of my small party of adventurers, but still fascinated by their banter and developing relationship.

Put simply, I think Enslaved widened its focus too much and lost sight of its characters, which are so clearly its key strength. To be sure, they’re a heck of a strength. They were easily enough to keep me hooked for the whole game. Not only is their dialog well-written, but Enslaved has learned from Uncharted’s presentation tricks when dealing with character animation. There are little details all over the place in Enslaved, as there are in Uncharted, that you simply don’t see in other games. Characters make funny glances at one another, eyebrows are raised in delicate expressions, those in the background react believably to what’s going on in the foreground, and subtle emotions like nervousness are unmistakably visible. This is all thanks to animation that is second only to the master, Uncharted 2, in terms of presenting characters that feel more real than any other game I’ve ever played.

But the story Trip and Monkey find themselves in does them a disservice by shoving them into the background toward its end. Things are only made worse by a narrative right turn out of nowhere at the finale that leaves the conclusion muddled and unsatisfactory. The game is desperately in need of an aftermath, some explanation as to what’s going on and what happened after the journey of the heroes concluded, but we get neither. After the credits rolled, I was sad my time with Trip and Monkey had come to an end, but angry that the game hadn’t managed to deliver any sense of satisfaction to what could have been a truly fantastic journey with the lovable duo.

As such, I’m reluctantly forced to relegate Enslaved to rental status. I still feel it’s a game worth playing. It does enough right, and enough things rarely done well in gaming, that it deserves to be played. Odds are, even with its problems, you’ll end up enjoying your experience with it. But when a game comes this close to narrative bliss and misses the mark, it’s made even more painful by thoughts of what could have been.